The Perfect Bullet.

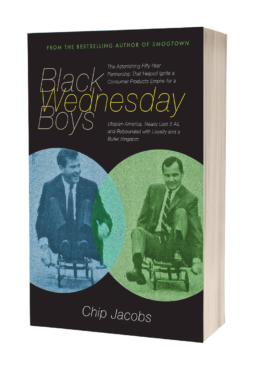

The Black Wednesday Boys is Jacobs' 2014 biography about Stephen Hinchliffe, Merle Banta, and their youth-driven company, The Leisure Group, the retail colossus that sorta was. Propelling it was an astonishing, fifty-year partnership that stoked a consumer products empire for a cash-flush America, nearly lost it all, and resurrected itself through uncommon loyalty (and devotion to the perfect bullet.).

“This book should be required reading for anyone who wants to learn what it takes to build an incredibly durable, valuable and nourishing long-term partnership. It is also one of the best books I’ve ever read on the challenges entrepreneurs face … Outsiders, including all too many journalists, imagine what it is like … This … shows vividly how tough that job really is and what it takes to succeed.”

— from the introduction by Gary MacDougal.

While this privately issued book is currently not for general public sale, anyone interested in obtaining a paperback copy may email chip@chipjacobs.com to request one.

CHAPTER ONE

Passengers boarding the red-eye out of Detroit Metropolitan Airport that September evening long ago had no idea what hardship had walloped the young executives in the aisle seats, but the men’s glazed expressions and trampled body language shouted that they needed to be given a wide berth. No bumping their chairs, no airy chitchat, no shifting their overhead baggage. The plastic-smiling flight attendants for TWA, Pan Am or whatever now-extinct airline booked them mid-fuselage already knew enough to keep their distance. They’d seen the walking dead before.

Earlier that Tuesday, the pair in loosened ties and sweat-beaded Oxford’s had been abandoned by a group of moneymen when they needed them most, leaving their company so destitute for cash that they’d have to fire virtually everyone upon touch down in Los Angeles. Thousands of innocent, blue-collar workers and the families who depended on them were about to be blindsided a few months before Christmas, to say nothing of the humiliation awaiting their bosses. On this Autumn day, the world’s sizzling news—the death of shoe-pounding commie Nikita Khrushchev, a new Disney theme park—was nothing more than Muzak to Stephen Hinchliffe and Merle Banta, the thirty-something MBAs with gloom die-cast in the faces. So excuse them if their knuckles cupped tensely around their briefcases. Pardon them if they crabbily rocked their nylon seats all the way back. Bankruptcy visions flashed before them.

In seven years together as entrepreneurs of a new economy, from the humblest beginnings to comers featured in Time magazine, never had anything mounted as catastrophic as this moment in late-September 1971. The coequal CEOs atop a pyramid that they’d scaled with grace, smarts, and brio were in a place they’d never been before: miserably exposed. Nick-of-time salvation, in this instance $35 million in bridge financing that they’d fully expected their financiers would lend them to spring back from an exceedingly solvable mess, had been stonily rejected. How could this be? Cash-flow shortfalls can roil any enterprise—a “Big Three” automaker, a Fortune 500 blue chipper, the corner hardware store. Now a few money-losing quarters, after six years of sensational returns that had dazzled Wall Street, the Rockefellers, the Warburgs, and other deep pockets, had gotten them dumped into menacing seas, palms gashed. Most infuriatingly of all, it was their local bank, First Western—the same bank that had hyped its role in The Leisure Group’s ascent into one of America’s fastest-growing companies—that had plunged them towards this ruinous hour. Begged for a lifeline, it’d given a blasé shrug. The treachery practically burned a chalk outline around the future.

None of this even felt possible, not when the slouching men until recently had been courted like princes. Early on, perhaps even too early, corporate stardom had wrapped itself around Merle and Steve’s efforts to capitalize on America’s accelerating love affair with disposable income by selling the Baby Boomer generation a robust collection of sporting goods, lawn and garden products, and toys. What had gestated in 1964 with a jury-rigged buyout for a dilapidated East Los Angeles sprinkler company had blossomed seven years later into a whirring manufacturing empire in seventeen regions looping continental North America. A methodical style honed at the elbow of their former employer, management-consulting guru McKinsey & Co., had whipped an initial $1 million in sales to $66 million in that period. If there was a ceiling over how high they could soar, it was paneled with ultraviolet-resistant tiles someplace in orbit.

But all that was gone with this flight to tomorrow. Once their jet landed at Los Angeles International Airport, they’d have to make the disaster official with required notifications. The same reporters who’d fawned over their innovative way of doing things would soon turn into vultures eying corporate road kill. After so many thrilling business trips when they’d been dying to get home to enact fresh ideas, the two could’ve used a weather delay. Besides harming people with no fingerprints on this bad dream, a more personal decision was already hurtling toward the pair. Should they stick together during the coming bedlam or, like so many others, detonate their partnership and drift away as embittered individuals? In Los Angeles, a showbiz town rent with juicy estrangements, some fates seemed unavoidable. Not even their ownership of the ultimate Hollywood magic—the Ruby Red Slippers from The Wizard of Oz that they’d acquired on gushy nostalgia—would confer any power to rescue them. It was their kinship, their bonding glue, which would have to prove heartier than dark circumstance, because their witches wore pinstripes.

From Black Wednesday Boys; copyright Chip Jacobs, 2014.

SELECT STORIES …

— “Hinchliffe Endowment Puts Scholarship First,” Occidental College, November 2011. Page 1, Page 2

— “Company Doctor: Merle E. Banta,” The New York Times, May 1984. Page 1, Page 2, Page 3, Page 4

— “The Oscar,” The New York Times, March 1981. Story

— “Judy’s Dancing Shoes Fetch Bid of $15,000,” Atlanta Journal. Story

— “Leisure Group Sells Yard-Man to Marcor. Says It’s Recapitalized,” Wall Street Journal, November 1971. Story

— “Leisure Group Reports Sharp Rise in Profits,” Los Angeles Times, January 1970. Story

— “Making Money on Leisure Time,” Business Week, January 1969. Page 1, Page 2, Page 3, Page 4, Page 5

— “Leisure: There Is Nothing Like a Game,” Time, September 1968. Page 1, Page 2