They found him on the sidewalk, a block from his boyhood home, with a shotgun blast to his handsome face and a gruesome wound through his chest.

Townsfolk skipped a breath hearing the news. Stephen Ballreich was hardly your ordinary murder victim, because Stephen Ballreich’s history had been so extraordinary. When he assumed Alhambra’s mayoral seat at just 26 in the mid-1970s, it sling-shot him to instant celebrity as America ’s youngest mayor, Golden Boy of the San Gabriel Valley, and who knew what else?

Charismatic and quick-witted, a natural before any crowd, the blond-haired, blue-eyed Ballreich had a seemingly limitless future. Congress, a run at governor: Republican pundits believed it was all his for the asking. Carelessness, however, would cost him almost all of it.

Shortly after his landside re-election in 1979, the electricity that’d once been around him turned to scathing headlines against him, as activists accused him of misspending city travel funds. The District Attorney’s office declined to press charges, but the scandal punctured Ballreich’s confidence. He abruptly resigned his post, relocating for ten years to Arkansas, where he’d later brag about hobnobbing with the Clintons.

Ballreich returned to Southern California in 1988 as a political consultant and a single dad, still dynamic as ever. Savagely killed at 41, he was never able to do what he confided to his girlfriend: seek office again.

If all this seems like a distant memory about a once-famous person, it is. Stephen (Steve) Lynn Ballreich was mowed down across the street from the leafy grounds of the Ramona Convent where he once played as a child on the night of Nov. 14, 1991.

Some 14 years later, the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Dept. remains stumped about who killed him. It is officially a cold case with no active suspects and no motive ever established. Several veteran homicide detectives assigned to the investigation have come and gone. One drifted into retirement feeling “haunted” by its unresolved status.

“All the leads have been exhausted,” acknowledged Sheriff’s homicide detective Susan Coleman. “We’ve been hindered by a lack of witnesses and evidence.”

So much time has elapsed since his execution-style slaying that a jaded sense exists today the case is almost unsolvable. Ballreich’s own mother has even stopped calling police for updates.

Adding to the cynicism is the virtual information blackout imposed by authorities. Neither the Alhambra Police Dept., which first responded to the shooting, nor the Sheriff’s Dept. that took over the investigation will release the crime report. Officials say publicizing it could jeopardize what leads they have, including clues lifted from the murder site, a modest, tree-lined neighborhood between Valley Boulevard and the San Bernardino Freeway.

At the top of the missing evidence is the murder weapon itself: a 12-gauge shotgun that cannoned two or three close-range pellet-salvos into Ballreich as he walked or jogged in the 1700 block Marguerita Ave.

“I ask some of the police chiefs once in a while when I am trying to be funny how the Ballreich case is coming,” said former Councilman Parker Williams, who served with him at City Hall. “You know without asking that nobody has any information … I think it’s just tragic.”

While several of his longtime friends question whether the Sheriff’s Dept. pursued the case as tenaciously it could have — especially in light of a newly disclosed 1989 death threat he allegedly received and his entanglement with several unstable women – it’s never been a slam-dunk whodunit. Ballreich’s habit of infuriating people he once impressed and his oft-murky doings made him a jigsaw-like personality excruciating for loved ones to piece together, let alone police.

Indeed, the more you dig into his existence, the more you see detectives’ quandary. It wasn’t so much who wanted Stephen Ballreich dead but, at times, who didn’t?

Williams, like others contacted for this story, said authorities told him that Ballreich’s killer probably first shot him in the back from a car, and then stood over him to bury a second round into his face. This blast penetrated his skull, blowing off the back of his head, according to the autopsy report, a copy of which the Pasadena Weeklyobtained.

In the days after the killing, wild theories circulated around town that a hit man hired by an obsessed woman, jealous husband, or incensed father was behind it, or that it came from a snowballing gambling debt. Fringe scenarios envisioned the ex-mayor targeted because of politics. Had Ballreich (pronounced Ball-ridge) been shot because he’d learned something sinister or switched allegiances?

For many, the fact that he died where he did was more than coincidence. People close to him knew he was so fond of his childhood block that he often drove from his sparsely furnished South Pasadena apartment, where he’d been living after returning from Arkansas, to exercise there. Had someone lying in wait exploited his nostalgia?

Authorities tried tempering the rabid speculation by suggesting it might’ve been a more mundane robbery or a gang assault. People who knew Ballreich’s past doubted it.

Besides, he was an athletic 6’2” Caucasian outfitted in a red jacket, sweatpants, and sneakers when he took his last stride. It didn’t fit the profile of a gangland assassination, even for a suburb a short hop from East L.A.’s deadliest barrios.

No, the way Ballreich died seemed to holler the motive — vengeance.

The local Baptist church that hosted his funeral drew 150 mourners, many of them numb. Eulogies by dignitaries from this gray, politically cliquish city lamented what was lost, what could have been. Less mentioned was the deceased’s compulsion for illicit romances and fast living. Those proclivities slid with him into the grave – or, perhaps, dispatched him there.

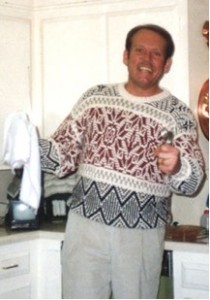

Stephen Ballreich in happier times om Dec. 31, 1990

A ‘HORRIBLE VOID’

Jo Hartman, a special education teacher in Santa Maria, remembers the heartbreak of 1991, when she breezed into her apartment to notice her answering machine blinking crazily. Played back, the messages had an awful theme — the local news was all over the story of her boyfriend’s death.

The two had been friends since tenth-grade algebra. Mischievous humor and chemistry kept them close but Hartman wouldn’t let it go further, knowing the pack of ladies who swooned for Ballreich without him even trying. One buddy compared him to actor Tom Selleck with a “Marlboro Man” swagger. You needed a calculator to keep up with his conquests.

It was in March 1991, after a fundraiser for a Pasadena candidate Ballreich was counseling, that romance kindled between him and Hartman. There was inevitability to it. They laughed they were the real life version of the movie “When Harry Met Sally.”

Ballreich, twice divorced by now, talked marriage, Hartman said. She wavered. They’d quarreled over money she owed him and his just-wing-it style. Hartman also recognized that Ballreich drank a lot, and had going way back.

She saw what others had. Binges and reckless abandon fueled the paradox about him, as if self-destruction was in his DNA. Ballreich could be tender and fun loving, the star of the room, just as he could be deceitful or a chronic flake that stood up friends.

Steven Born learned this about him in the early-1970s. They’d met as volunteers for the Young Republicans doing grunt work on a congressional campaign. Born watched his friend alienate peers with sordid behavior that undercut what he said was Ballreich’s uncanny “power of persuasion. ”

“That was part of the problem: (Steve) could manipulate people so well,” said Born, a science teacher in the San Fernando Valley. “He remembered everybody’s name. He could get people to do things and work hard on campaign, even for inferior candidates. He was a wonderful salesman There was that a part of him that did really care about people. Then he’d switch on the selfish part and regret it later. It was like he was telling himself he had to do that to be a good person.”

In July 1991, the last time Hartman saw him alive, Ballreich unexpectedly — and for reasons still unexplained — asked her to witness a will that he’d had drafted. By the fall, the pair had started to warm up again. He was chipper about his future, telling Hartman that he wanted to “toss his hat in the political ring” a final time without specifying which race.

Ballreich’s last communication with Hartman was a funny Halloween card he mailed. Her final words to him were a phone message that went unreturned. She left it on Nov. 14 at 6:51 p.m., roughly 90 minutes before his murder.

“I was in despair, beyond despair with the news,” Hartman said. “At first I didn’t believe it. At the reception after the funeral is when it hit me. He was really gone! It was that horrible void. ”

Hartman said she spoke to the police several times trying to aid them. Another longtime friend, who asked that their name be withheld out of safety concerns, joined in. This friend sent detectives a nine-page memo listing Ballreich’s friends, associates, and lovers, theorizing who might have wanted to have hurt him. The memo, a copy of which the Weekly has obtained, points most strongly at two women with whom he’d been involved.

The Weekly does not divulge the names of people if they have not been arrested or sentenced for a crime.

Ballreich had met one of the women when he was a twenty-something mayor and she was a petite, attractive teenager from a local high school. They dated periodically and often brazenly. The relationship notched doubts about Ballreich ’s character within the city’s Establishment.

“He screwed himself up at an early age with drinking, gambling, liking young girls,” said Barbara Messina, a former councilwoman and current Alhambra School Board member. “He had too much too soon and couldn ’t handle it.”

RED FLAGS

According to the memo, this younger woman later studied the cello at USC, but never finished there because of drug problems. She eventually married someone else and moved to the New York area. Even so, she and Ballreich continued their love affair. Their favored spot was a room at a Best Western motel in Arcadia, the memo said.

In Jan. 1989, this woman’s husband allegedly threatened to kill Ballreich if he continued the tryst, the memo said. Ballreich, worried enough to interview bodyguards, told the friend who wrote that memo that the woman was in town at the beginning of Nov. 1991 and that he had seen her.

“Obsessed with Steve, extremely possessive, constantly looking for Steve’s suspected infidelities despite (the) fact that she, herself, continued to be married,” the memo read. “Violently jealous … (Steve) described his continuing concern for her welfare as his ‘weakness …’”

Hartman said Ballreich never told her about any threat, but she knew about the woman. A few years earlier, when she and Ballreich were just friends, she’d called him about playing tennis. He abruptly told her he couldn’t and hung up. Hartman’s phone soon rang and Ballreich put the woman on the line.

“She said, ‘This is so and so and I’d like you never to call Steve again,’” Hartman recalled. “She said, ‘He’s my fiancé and I want you out of my life.’ It was almost like Steve was intimidated. I said Steve’s happiness is important to me and if I’m upsetting that, I won’t call again. She slammed the phone in my ear. Steve called the next night to say he was ‘horribly sorry.’ I told him, ‘Steve, what are you doing? This was a red flag. ’”

Hartman said detectives informed her that when they questioned the woman about her whereabouts and activities the day Ballreich died, she warned them that the next time they called she’d have her lawyer represent her.

“As soon as she said that, they stopped. To me that would’ve been pay dirt,” Hartman said. “They should have been running this down. I’m not blaming the police. I thought it was one of those hard-to-solve cases. But there was a real suspect and the Sheriff’s Department didn ’t follow through.”

Both Hartman and the friend who wrote the memo said they asked detectives if a crime show like America’s Most Wanted would air a segment on the case to generate leads. The friends said the idea went nowhere because detectives told them that producers of those shows didn’t feel Ballreich was a sympathetic-enough victim.

Ballreich’s friends also informed detectives that someone had plundered his South Pasadena apartment after his murder. Hartman, who had her own key, said she went to retrieve his will on Nov. 16 and it was gone. When she returned the next day, it’d reappeared. In the memo to police, Ballreich’s other friend reported 10 items missing from his place. Among there were a gold watch, two rings, a bible with his daughter’s name in it, a pair of negligees, and, curiously, his address book.

“His apartment wasn’t taped off,” Hartman said. “There was no yellow (police) tape.”

The Sheriff Dept.’s Coleman defended how Ballreich’s apartment was secured, saying “the appropriate avenues” were maintained. She would not elaborate on the items allegedly taken. Sheriff’s Dept. officials also refused to specify what tips from Ballreich’s friends they’ve used. Neither would they confirm whether a volatile, older woman from the political world that Ballreich had slept with had passed their polygraph test under interrogation.

“There were several friends, several associates and several acquaintances who were interviewed by us, but no one has been identified as the suspect,” Coleman said. “There are many things that could have happened, and maybe even the thing you expected least. You just can’t have guesses. You have to have facts.”

As with all unsolved murders, detectives have reviewed Ballreich’s case within the last five years. Coleman said they didn’t find anything had been overlooked.

PROJECT PRIDE

Stephen’s mother, Jean, said she’s lost track of the hunt for her son’s killer. For the three years after it happened, she said she stayed in touch with authorities from her home in Prescott Arizona. A highly devout Christian, now twice widowed, she moved to the Southwest in 1980 to ease her asthma.

“At first, I really, really wanted to know,” she said. “I would keep calling the Sheriff’s Department, and the detective said, ‘As long as I’m here,’ they would pursue it. There are many things about it that are hard to understand.

“But it won’t bring (Steve) back. God knows all things, and he knows what happened. If I could talk to whoever did this, I would just say I forgive you, not because I because I didn’t love my son, but because God will.”

She and Stephen’s father, Barney, had once foreseen great things for him. From an early age, he schmoozed neighbors on his paper route, had terrific writing and speaking abilities, and possessed a magnetism everybody recognized. Shackling those talents, his mother said, was a manic-depressive streak and pigheadedness from an early age that he was destined for life in politics and only politics.

The family’s Beverly Hills-based jewelry business disinterested him. Ballreich’s father died suddenly when he was in his early-twenties.

“From the time he was born, a lot of his problem was being too high or too low. I couldn’t convince a lot of people about that,” Jean Ballreich said. “Emotionally, he was unstable. If he hadn’t been that way, he might’ve been the governor of California. I would’ve loved it if he’d gone into TV.”

One matronly Republican Party volunteer remembers meeting Ballreich when he was a gung-ho teenager with a cast on his leg stuffing mailers for a conservative candidate. Ronald Reagan and former Sen. Barry Goldwater were his icons. He quoted Thomas Jefferson the way some teenagers quote rock songs, though Stephen was a Beatles fan entranced with the White Album. He collected political pins, assembling an impressive collection.

Despite obvious brains, his grades were average, his mother said. After graduating from Alhambra High School, he attended various colleges without earning a degree.

To make money – and he always seemed to scrambling for it — he owned a Burbank restaurant named the Pizza Pantry. He did seasonal campaign work for local Republicans as well, and may have taken odd jobs under the alias “Richard Aldridge,” sources said.

He married young, but the union was stormy, and he and his first wife, Cindy divorced. She did not respond to requests for comment.

“He wasn’t a follow-througher unless it was something he wanted to do,” Jean Ballreich said. “Politics ruined his marriage. He gave Cindy a bad time. He did so many contradictory things.”

It was in 1974 when Ballreich blindsided the Alhambra Establishment by unseating incumbent Councilman T. D’Arcy Quinn. He used hustle and chutzpah to win, staying up to 4 a.m. election-day dropping campaign fliers on doorsteps. When he became mayor three years later, he was suburbia’s boy wonder. The local Jaycee’s named him one of California’s “five most successful young men.”

Ballreich’s signature initiative was “Project Pride” a community cleanup regimen. Local TV stations did segments showing him painting over graffiti with ex-gang members.

Parker Williams said he introduced Ballreich about this time to noted political consultant Stuart Spencer, who’d later advise Reagan as President. Spencer, Williams said, thought Ballreich had a sparkling career ahead if pushed aside the distractions.

A record 75 percent of voters in his district re-elected him. Politically, it was as good as it got. Three months after his victory party a citizen’s group called “All We Can Afford” accused him of misspending and failing to report $2,650 in travel expenses.

A District Attorney inquiry netted no formal charges. Prosecutors never turned up any proof that Ballreich had intentionally broken Alhambra’s then-vague travel rules. Ballreich took it on the chin, nonetheless, and summarily quit the council – a decision he said he later regretted.

From there, the city’s chastened prince did the unexpected. He picked up his things and hotfooted it to Arkansas.

DREAMING GRANDLY

He was in the South most of the 1980s, doing what nobody is quite certain. He told everybody different stories, the truth nuanced or wholly concocted, maybe to cover his tracks, maybe to cover his shame about blowing his chance back home.

What is known is that he stayed in a house his mother purchased in a lake-edged resort town called Heber Springs, in Arkansas’ north-central Ozark Mountains. He also spent time in Little Rock, apparently doing campaign work for state Democrats. Interspersing that was a job as a radio talk-show host, even if no one remembers the station or the show format.

Born visited him in Heber Springs in 1988. As usual, Ballreich didn’t show up to their agreed meeting place, so Born asked a local where he could find the town’s big radio personality.

“The guy laughed,” Born recalled. “He said Steve fries fish for a living.’ I thought typical Steve.”

Wherever his paycheck came from, Ballreich spoke constantly about associating with then-Gov. Clinton and his wife, Hillary. Depending on whom you ask, he worked for him, advised him, or merely socialized with him.

There certainly were striking similarities between the two men. Both were political junkies, professionally ambitious, magnetic one-on-one and, often, good-time charlies.

“If you were in a crowded room with Bill Clinton, he’d talk to you like you were the only one there, and Steve was the same way,” said Glenn Thornhill, who knew Ballreich from his Young Republicans days. “Steve said he knew Bill and Hillary, and hung around in the same circles. Who knows? It could’ve been bull. But I can see why Steve liked him: Clinton was a successful Steve Ballreich.”

While in Arkansas, Ballreich had a daughter, Noelle. One source said he wed the mother in a shotgun marriage that did not last very long. Before he died, he admitted he’d been an absentee father, and at least the girl wouldn’t be influenced by him.

There wasn’t always so much clarity. Ballreich, for instance, tried convincing folks he was part Irish in spite of the imposing, blond appearance that confirmed his German heritage. He compartmentalized his life so slickly that longtime family friends had little inkling of his wild side or the fact that he’d done semi-pro boxing.

Most everybody knew about his sexual appetite. He’d say that when his “hormones percolated,” he was at their mercy.

“Light and dark,” one family friend used to describe him. “Light and dark.”

Arkansas’ weather and cultural climate helped propel him back to Southern California. He returned poor, but with his love of politics and patriotism intact. He stayed with friends at first, until he had enough money to rent.

If he lived cheaply, he dreamed grandly. Ballreich in early 1989 hooked arms with failed Alhambra Council candidate Allen Co in a novel bid to boost voting rates and political participation within the city’s Asian American community. It was a prescient move; Asian-Americans today comprise 60 percent of the town’s population. Ballreich told reporters he was stunned by the level of prejudice among whites and the surge of Asian businesses since he’d left, and that someone had to usher in the future.

Co, who later served on the South El Monte Council, did not return phone calls.

Ballreich’s energy crackled elsewhere. In 1988, he and Merrill Francis, a longtime Alhambra lawyer and civic leader, launched a political consulting business called Pegasus. Their gimmick was that Francis was a Democrat, Ballreich the Republican, with a wealth of campaign experience between of them. Together only a few years, they mostly ran local council and school board races, branching out to manage then-Councilman Michael Blanco’s losing bid for California insurance commissioner.

Francis said he has difficulty recollecting Ballreich’s murder because it coincided with the death of his first wife and his mother. Some things haven’t dimmed.

“Steve was very approachable and there was an excitement about him – a sex appeal,” Francis said. “He made a strong impression.”

There was no question, Francis said, that Balllreich was a “lady’s man with a pretty active social life.” At the time of his murder, Ballreich had been dating a younger woman who worked in the court system, Francis added. He did not know if the police spoke to her.

Authorities did disclose to Francis that Ballreich’s answering machine tape had given them promising leads. They said the murder had the earmarks of a “professional job,” what with shots to his face and heart area.

During their span together, Francis said that Ballreich had traveled around the country promoting a patriotic cause for a man who later refused to pay him. Though angry about being stiffed on that job, Ballreich routinely took chances like this, chances that almost no one else would, be it with spec jobs, pranks, or women half his age. It was as if he needed the adrenaline kick of risk to feel whole.

“Steve was a natural risk-taker,” said Francis. “He’d bet beyond his paying capability. One time he put up the pink slip on his car on a prize fight … What I’m seeing (today) is that he was a like a piece of quartz shining through many facets.”

Francis, now 72, spoke at the funeral and tried assisting police. He doesn’t subscribe to what he calls conspiracy theories that Ballreich’s murder was politically motivated.

“That scuttlebutt didn’t mean anything,” he said. “But there is disappointment there hasn’t been retribution for whoever killed him.”

Ballreich’s affection for Clinton did not dip when he hit California line. He told many, including Francis, in 1991 that he would not only back Arkansas’ governor for President – he would raise money for him.

If Ballreich was on the Clinton team, it’s news to some of the his key advisers. Los Angeles lawyer John Emerson, who was involved with Clinton’s 1992 campaign to win California, said he didn’t know who Ballreich was. Linda Dixon, assistant manager for volunteer and visitor services for the Clinton Foundation, parroted the same line.

“I’ve been with President Clinton 23 years and I’ve never heard his name before,” Dixon said. “I’m only speaking for myself.”

Ballreich’s Young Republicans chums kept in contact with him to the end. Over drinks, they razzed him about how a died-in-the-wool conservative could support Clinton. They noticed that while he was still the impulsive, womanizing guy he’d been before, he had a more serious bent to him, a sort of “world-weariness.”

DIFFERENT STORIES

His death was quick, brutish, and seemingly well orchestrated. Residents who heard the shots summoned Alhambra police. Witnesses said they’d seen a dark, 1970s-era Camaro fleeing the scene. Nothing came of that lead.

Fear clenched Marguerita Avenue in the aftermath. The nearby elementary school — the same one Ballreich attended in the 1960s — went into lockdown after someone reported a prowler lurking. It was not the last suspicious sighting, not with a murderer running loose.

Police discovered Ballreich lying face up with what the coroner’s office said was “massive open head trauma.” The second wound came from a shot that struck him in the upper left side of his back and exited through his chest leaving a roughly seven-inch gash. Either of these gunshots was lethal. Police extracted gunshot residue from the scene.

The autopsy report said three salvos were fired, but only described two of them. Ballreich, it said, appeared to have been “walking on the sidewalk” when he was killed. This may be critical. While he was an avid runner, he was wearing underpants, not an athletic supporter, at the time he died. Some have wondered was whether he was meeting somebody.

No drugs were detected in his system. Overall, the autopsy determined that Ballreich had been healthy. He still carried his Arkansas driver’s license.

Detectives mulled the possibility street gangs had been involved. Four days before Ballreich’s murder, a 20-year-old gang member had been killed about a mile away.

Detectives also interviewed members of the Lincoln Club, a Republican political action committee that Ballreich volunteered at and advised. Before he’d died, he been counseling the PAC about candidate donations and its involvement with campaigns.

One former worker there said detectives interviewed employees individually at the club’s El Monte office. Nerves were already on edge at the small organization after employees complained about a bizarre series of petty crimes launched at them. Employees, according to this former worker, reported a slashed tire, a tampered gas tank, a stolen purse, and signs of an intruder at one of their houses, among other unexplained events. Suspicion fell on a recently fired club employee – a woman who’d known Ballreich well.

Bill Ukropina, a volunteer with the Lincoln Club and former chairman of it’s Pasadena branch, said he did not recall the Ballreich investigation touching the group. Nor, he said, was he aware of Ballreich’s personal problems.

“I never saw any side of Steve other than a cordial, professional one,” Ukropina said. “He was such a talented guy. He made excellent presentations. He brought a lot to the world, a lot to the community. I miss him.”

Ultimately, the Sheriff’s Dept. discounted both the Lincoln Club and gang violence as probable connections. It was not clear why detectives ruled them out.

Which leads us back to the beginning — November 1991. If it wasn’t a drive-by, and it wasn’t something else random, who then killed him Stephen Ballreich?

We may never know.

When you sweep aside everything else, you see he died the way he’d lived — spectacularly, disturbingly. And that how he lived confused the search for whoever took his life steps from where he’d grown up as his city’s can’t-miss kid. It’s symmetry not lost on old acquaintances of his.

“One of my friends ran into an Alhambra policeman, and the cop said, ‘We don’t know who did it,” Glenn Thornhill recalled. “Steve Ballreich told so many different stories to so many different people we could be talking to the responsible person and we wouldn’t even have a clue.’”

Anybody with information about this crime can call the Sheriff Dept.’s Homicide Bureau at (323) 890-5500.

The Pasadena Weekly published a shorter, slightly different version of this story. Copyright Chip Jacobs

Related Posts

The Brown Air Prequel for our Climate Change World

Why the Sky Disappeared, and Why L.A.'s Smog-Choked…

At Christmas, “It’s A Wonderful Life.” In 2022, hopefully it’ll be a series about a life as Impossible as it is Strange!

Mercury Media has optioned its inaugural title, the…