When word broke three years ago that the poison Erin Brockovich had fought in tiny Hinkley, California had also contaminated groundwater supplies in the dense San Fernando Valley, the countermeasures rippled through California officialdom with a panicky speed.

Wells were closed. Hearings were convened. Laws were passed. Sales of water-filtration kits boomed. Everybody, it seemed, was talking about the perils – or the unwarranted hysteria – created by hexavalent chromium, a versatile industrial compound used by Valley manufacturers, particularly those in the former Cold War aircraft production business.

The yellow-green stuff made infamous in Brockovich’s biographical movie, popularly known as chromium 6, exudes no odor or taste. Health officials long ago listed it as a powerful carcinogen when inhaled as dust. Whether it causes serious illness when consumed in water is officially unknown, despite years of concern.

With federal eyes fixed these days on homeland security and the state focused on other toxins such as perchlorate – a rocket-fuel booster that has permeated sensitive areas from Azusa to Pasadena to the Santa Susana Pass on the border of Ventura and Los Angeles counties – hand-wringing over what to do about chromium 6 has receded from the mainstream agenda. Yet the situation – both underground and in Sacramento’s policymaking world – remains anything but static or calming, a CityBeat investigation has found.

While tap water tainted with significant concentrations of chromium 6 hasn’t yet materialized, previously skeptical local officials now acknowledge that groundwater deep under Burbank, Glendale, and the northeastern portion of Los Angeles will eventually be flooded with so much affected water that officials will be forced to seal off wells and import costlier water from the Metropolitan Water District.

Doing that countywide could add hundreds of millions of dollars to ratepayers’ and government bills, to say nothing of the public health debate – and neighborhood-level fright – it would rekindle.

“It means costs will go up dramatically,” perhaps fourfold,” said Tim Brick, an MWD board member and longtime Pasadena environmentalist. “Then they have to deal with the hassles of developing cleanup programs.”

That hassle is a matter of when, not if.

A sobering, yet surprisingly little-noticed report by the longtime custodian of the Upper Los Angeles River, combined with the results of a four-year investigation by regional water quality officials, depict a menace that won’t wait for long-term fixes. In blunt language that sounds more like a wartime call for action than a plea for more number crunching, the Water District’s January 2003 study titled “Watermaster Special Report Concerning the History and Occurence of Hexavalent Chromium Contamination in the San Fernando Basin” warned that a series of chromium 6-laced “plumes” are surrounding wells in the Valley faster than expected. As a result, there is a “clear and present danger” to area water supplies that hundreds of thousands of people and businesses rely on daily.

“Unless immediate regulatory action, on both state and federal levels, is taken to remediate the hexavalent chromium contamination in the eastern portion of the basin … wells … may have to be shut down …” says the report. “The contaminant plume, identified in historic test results, poses a clear and present danger to our drinking water supply.” New treatment facilities will cost millions, if not much more.

If local water engineers are unsure what to do, state executives in charge of the hard science are lagging badly behind in their efforts to guide them. A definitive standard for chromium 6 in all California drinking water was legally required to be on the state books by January, but now appears to still be several years away. Meanwhile, a report assessing the severity of the Valley’s groundwater problem with chromium 6 remains unfinished, more than two-and-a-half years behind schedule.

“It really is quite amazing to me that the Department of Health Services (DHS) had a legislative mandate to determine the level of chromium 6 in water and report back to the Legislature and the governor in 2002 and never did so,” said that law’s author, Rep. Adam Schiff (D-Pasadena). Schiff was a state senator representing Glendale and Burbank when he wrote the bill. “Even the straightforward matter of reporting the concentrations in the San Fernando Valley hasn’t been done,” he said.

DHS officials refused to offer specific explanations about the delay or allow their drinking-water chief to be interviewed. They note they have posted chromium 6 samplings statewide on their website (www.dhs.co.la.ca.us).

‘Lots of heat, little substance’

Clustered between North Hollywood and the Glendale-Los Angeles border, and more or less along the flange of the Golden State (5) Freeway, the chromium 6 plumes could turn a huge part of an aquifer into a mothballed toxic swamp. Until now, local cities have addressed the problem by blending tainted water with purer sources.

Filtration plants that are operated under the federal Superfund program can’t cleanse the water of chromium 6, largely because they were built to purge other dangerous materials called volatile organic compounds. There is no current off-the-shelf technology to filter chromium 6 to trace levels without causing difficult waste issues, though research is barreling forward.

“Without timely remediation efforts, the contaminant plume will continue to migrate, causing detections of hexavalent chromium in groundwater wells at such high levels that blending water with other sources may no longer provide a feasible solution that enables the continued delivery of water meeting state and federal standards,” watermaster Mel Blevins wrote in his 2003 report. “Given the hydrology of the basin and the hexavalent chromium concentrations up to 156,000 parts per million in soil and one million in groundwater, the imminent threat is … clear,” the report adds.

Among the major points in his study:

*Water technicians suspect defense contractors such as Lockheed-Martin Corp. and Menasco Aerosystems, and others such as Drilube and Excello Plating, created the “hot spots.” (Some of those manufacturers no longer operate in the area.)

*The waste was discharged into storm drains leading into the Los Angeles River, or dumped elsewhere from World War II to the 1960s, an era predating strict environmental rules. Once in the aquifer, the chemical seeped easily through the stratum partly because of the chemical’s solubility, and partly because the alluvial soil lets it pass through swiftly. The plume is moving on a general northwest-to-southeast bearing.

*Blevins himself testified that he had “personal knowledge” that Lockheed, Andrew Jergens Co., Knickerbocker Plastic Co., and Sears, Roebuck and Co. extracted groundwater for use in their cooling towers and then returned the wastewater into the ground.

To display his seriousness about the issue, Blevins had engineers with long histories with water-contamination issues give their statements about chromium 6 as sworn declarations, meaning they would face perjury charges if it were proven they lied.

“During my visits to Lockheed and Menasco, and during my employment at North American Air, I observed that all of these companies used chromium 6 within ´´ the [Upper L.A. River area] for anodizing aluminum,” testified William Garber, a veteran city and county chemist with more than 40 years experience. “The waste water regularly spilled onto the ground, enabling chromium 6 to enter storm drains or percolate into the soil.”

William Ree, a longtime DWP engineer, testified he saw chromium 6 in the Burbank Wash close to Lockheed’s operations. Generally, chromium 6 is not visible in water unless it exceeds 1,500 parts per billion (ppb), Ree said.

“Because of the high concentrations of chromium 6 in the Wash, I suspected that the Wash was being utilized by industrial organizations as an open source for the dumping of constituent chemicals … Indeed, I observed that the same green/yellow coloring in the waste stream flowing from Lockheed’s facilities flowed directly into the Wash.”

Like the residents of Hinkley, people in Burbank know that chromium 6 is not an abstract issue paraded by extreme environmentalists.

In 1996, Lockheed forged a secret, out-of-court settlement for $60 million with more than 1,300 Burbank residents who claimed they developed cancer and other illnesses, plus suffered property damage, from the company’s industrial waste disposal practices. The retired judge who mediated the case, which bred follow-up lawsuits when word leaked out, said chromium 6 was the catalyst. But it had been assumed that chromium 6 got into the neighborhoods through air emissions.

Pressed about the issue, Lockheed executives later said that wastewater laced with the chemical was discharged into the Valley’s aquifer from the company wells at its former “B-1” plant. Lockheed used chromium 6 as an anti-corrosive in its air conditioning system and in wind tunnels until the mid-1960s. Lockheed has spent close to $275 million on solvent cleanups in Burbank and paid out roughly $100 million in health claims to workers and residents. The company moved its Burbank operations, which developed famed aircraft from the SR-71 Blackbird to the Stealth F-117 fighter over the decades, to Georgia in the early 1990s.

In an interview, Blevins said because the three area cities have been able to blend the chromium 6 water to well below existing state standards, there wasn’t much hue and cry about the tardy Department of Health Services report. The Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, he said, has shuttered about five to 10 wells out of precaution.

“If the cities aren’t fussing about it, I don’t know how DHS would feel any concern,” Blevins added. “I don’t know if they are sweeping it under the carpet, but you can get blindsided by [this issue]. I have studied the groundwater problem in the San Fernando basin for many years and I don’t believe it’ll be a long time before we have to deal with high concentrations of hexavalent chromium. We’re talking five to10 years before the plume is right there at these wells.”

Worries about the health impacts of chromium 6 led Glendale to dump 4,000 gallons of polluted water per minute into the L.A. River for much of 2001 – a cautionary move that put the city at loggerheads with federal authorities and others.

Next door in Burbank, despite some disbelief about the dangers of the chemical, two wells were closed, and blending has since kept chromium 6 at trace levels.

Fred Lance, Burbank’s assistant general manager, said there was “lot of heat and very little substance” following an August 2000 Los Angeles Times exposé about state delays regulating chromium 6. The story triggered meetings, legislation, pleas for investigative funding, and public demands for action, all of which seem to have fallen off the public’s radar.

“Our numbers are below state standards,” Lance said. “This is not Hinkley.” In that remote San Bernardino desert town, Brockovich found dumping practices by Pacific Gas & Electric had poisoned hundreds of people. Even so, Lance conceded, “both Glendale and Burbank are sitting in the middle of the plumes and we are concerned about losing our production facilities.”

Just last month, the MWD’s efforts to get the state’s toxic-control department to attack chromium 6 pollution at a Pacific Gas & Electric compressor site at the lip of the Colorado River went public. A plume with concentrations as high as 13,000 ppb was detected at a sentry well within several hundred feet of the river near the California-Arizona border. MWD officials, who termed it an “emergency situation” in their correspondence, were able to get the utility to start pumping out the tainted water before it leached into the groundwater table that feeds millions of Californians. PG&E discharged the chromium 6 after using it as a rust-inhibitor, said Bart Koch, MWD’s water quality lab manager. More than 108 million gallons of untreated wastewater containing chromium 6 were discharged into percolation beds between 1951 and 1969.

Dropping the ball

Chromium 6 is an established carcinogen linked to lung cancer and other respiratory-tract ailments when inhaled. Whether it causes stomach, throat, and other forms of cancer when ingested through drinking water remains the subject of fierce debate at the state and national levels. A federally run toxicology study on this question is expected to wrap up in 2005. Schiff and U.S. Senator Barbara Boxer pushed for the study.

Some scientists argue chromium 6 shouldn’t be in the water at all. Others argue that stomach acids render it into a benign form of chromium, which is a natural substance.

Adding to the confusion, some say merely breathing shower mist exposes people to potentially deadly effects. Others contend chromium 6 contamination is an over-hyped fear stirred by the media and Hollywood.

State law limits total chromium in drinking water, as a way to contain chromium 6, at 50 parts per billion. The federal cap for chromium exposure is 100 ppb. In 1999, California environmental officials ignited controversy when they proposed slashing the limit to 2.5 ppb. They later withdrew that initiative, admitting they dramatically underestimated how much chromium 6 made up total chromium in California water.

Today, the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment is still working on a threshold for chromium 6, a heavy metal that has turned up in manufacturing-rich states from New Jersey to Texas to California.

Its prevalence in groundwater stems largely from its “do-it-all” capabilities. Among other uses, chromium 6 has a long history in industrial chrome plating and welding, as a paint pigment, and in leather tanning. It is also used as an anti-corrosive.

Blevins, who is now a consultant after 23 years as watermaster, expressed some surprise at the “hot spot” readings that his research uncovered during sample testing from the late 1990s to a few years ago. At Lockheed-Martin’s former aircraft manufacturing complex near the Bob Hope Airport in Burbank, it was 440 ppb. At Drilube in southern Glendale, samples registered 72,380 ppb. A test well operated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in that city clicked in at 1,200 ppb.

Current readings are well below those alarming samples, with “hot spot” numbers ranging from 15 to 780 ppb. Seven of the hottest sites are under a cleanup and abatement order by Los Angeles Regional Water Quality Control Board, which investigated 225 suspected sites and has winnowed that number down to 105 requiring further assessment.

Under Schiff’s bill, SB2721, the state Health Department should have been conducting similar sampling, but has yet to file a report for public consumption. “It’s disappointing the state Department of Health Services has dropped the ball on this,” Schiff said.

For reasons state officials have declined to specify, the completed report that Schiff ordered remains “under review.” Sources told this newspaper the report went to Governor Gray Davis while he was still in office, but that it was “bottled up.” ´´

“Since it’s not complete, [the report] is nota public document,” said DHS spokeswoman Lea Brooks. “It’d be inappropriate to comment until then.”

The Missing Report

Alise Cappel, research director at the Environmental Law Foundation in Oakland, said she was “floored” when she read Blevins’ report. (Interestingly, the Times, which has written extensively about chromium 6, only did a brief piece on the report when it was released.)

“What caught my eye was the proximity to the wells and the tone in which it was written,” said Cappel, who has bird-dogged the state’s effort to regulate chromium 6. “I’ve talked to Mel Blevins. He’s old school. He’s not one to be an alarmist.”

Still, not everyone agrees the region is teetering on the brink of disaster.

Gerald Gewe, head of water systems for the powerful Los Angeles Department of Water and Power, said Blevins’ report was intended to galvanize federal officials in getting a cleanup started. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency does not formally consider chromium 6 to be a cancer-causing agent after it is ingested as drinking water.

“Unfortunately, government doesn’t react well in terms of a crisis, so sometimes you have to over-paint something to get attention. Our water is within standards. I drink it,” Gewe said.

The state’s lengthy process to develop a drinking water standard for chromium 6 probably won’t be supplying authoritative answers soon. One of the main reasons for that is a study by a blue ribbon panel convened by the University of California concluded that the chemical was not a carcinogen when ingested orally. However, that study was later discarded because of revelations that PG&E-paid consultants staffed the panel and manipulated the results.

Under state law, the first step in establishing a limit for drinking-water agents is to develop one that would pose no health risk. This is called a Public Health Goal, and is established by the state’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment.

Dr. Joan Denton, head of that office, said that goal probably wouldn’t be set until sometime next year, after scientists are finished poring through years’ worth of studies. From there, the Department of Health Services gets involved, using the health goal, cost-benefit analysis, and feasibility to calculate the eventual numerical limit of how much chromium 6 can be allowed into drinking water.

Denton and other sources said it’s unlikely that limit would be in place for a couple of years. “To be quite honest, [the controversy over the blue ribbon report] delayed work on the Public Health Goal,” Denton said in an interview last week. “When we received the blue ribbon report, we took it quite seriously. We were going to use the same group to peer review. Hexavalent chromium is a huge issue. Now it has this past history.”

State budget cuts that eliminated staff positions and outside experts, Denton added, have also slowed progress on the health department’s goal.

Denton said her office furnished data to DHS’s report about Valley chromium 6 contamination. Local water officials did as well, and it mystified them when no finished report was ever passed around. All they saw was a draft copy that they weren’t allowed to keep.

“I’m not aware of anything controversial in the report,” Denton said. “We provided our piece to the Department of Health Services and it was up to them to follow up.”

Whatever the reason, snafus codifying a threshold for chromium 6 in water have left local cities in limbo.

Do they continue funding a pilot research program to purge low levels of chromium 6? Do they pursue corporate polluters, as Glendale and Burbank intend to do? Do they map out contingency water supplies? Under legislation by state Sen. Deborah Ortiz (D-Sacramento), that standard was to have been in place by January.

“It would have been a greater comfort level if we had a standard,” said Don Froelich, the recently retired chief of Glendale’s water system. “We would have preferred the state would’ve met their schedule, but we understand their situation.”

Six of Glendale’s eight wells, he said, register for chromium 6 at 5 to 6 ppb. The other two wells, he said, register at around 50 ppb each, a problem city water officials hope to mitigate even further by thinning existing resources with water purchased by the Metropolitan Water District. Those two wells now produce low levels of water for community use, and there are as yet not additional costs to ratepayers.

“Our biggest concern is if these chromium 6 levels increase, because we know we have high levels in our groundwater,” Froelich said, adding he did not believe the somewhat dramatic language in watermaster Blevins’ report was exaggerated. In fact, the city, along with Los Angeles and Burbank, are waiting for a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency engineering report on the extent of chromium 6 contamination in the San Fernando Valley.

The watermaster’s report, Froelich added, “Is all part of trying to document who is responsible for creating the problem … and who is going to pay for the cleanup. We agree with it,” he said of the report’s findings. “It’s real. It’s just a matter of how long it’s going to take for [chromium 6] to get to the production wells.”

‘A clearly biased panel’

The blue ribbon panel’s August 2001 report, which asserts chromium 6 is not a carcinogen through water, still haunts state scientists.

Formally called the Chromate Toxicity Review Committee, the group was primarily composed of University of California professors and scientists. Their conclusions appealed to chromium 6 skeptics, primarily because they cited the inadequacy of a 1968 German study that the state banked on in proposing the now-withdrawn public health goal for total chromium.

In that German study, mice that were fed large doses of water contaminated with chromium 6 developed stomach tumors. After reviewing that study, the chromate committee said a virus that hit the mice might have caused lesions that German researchers mistook for chromium-induced tumors.

But last spring, those who were behind those conclusions became a news story themselves.

Gary Praglin, a Century City attorney who worked with Ed Masry, his legal aide Brockovich, and prominent Los Angeles tort lawyer Thomas Girardi on the Hinkley case, found PG&E had manipulated the panel by stacking it with two paid consultants. The two consultants had earned millions from the utility for their chromium 6 expertise then wrote two chapters of the blue ribbon report verbatim from previous work, e-mails retrieved during that case’s discovery process proved. A supposedly neutral association of concerned parties turned out to be a “front” for industry, Praglin found.

Most shocking, though, was that one of the committee members never disclosed that his former consulting company had been paid by PG&E to write a follow-up report of a 1987 chromium study by a Chinese scientist. That scientist, Jiandong Zhang, reported elevated cancer risks and various stomach disorders after 300,000 tons of chromium waste was dumped in areas of the eastern city of Jinzhou.

Yet in the follow-up study that California officials believed Zhang authored, those findings were reversed. Zhang, who Praglin believes is now dead, did not speak or write English, and his name had been misspelled in his supposed follow-up work. It turned out he’d been paid by PG&E’s consultants, too.

Smelling industry infiltration, Ortiz denounced the panel’s report, which was later thrown out. John Froines, a UCLA professor and head of the school’s center of occupational and environmental health, quit the committee, largely over his concerns about alleged conflicts of interest.

“We threw questions into what was clearly a biased panel,” Ortiz said in an interview last week. “The antics and contrivances [were] even more appalling because the public is relying on the state of California to protect its health. They are entitled to having deadlines met.”

PG&E, which did not return calls for this article, at the time called the influence peddling charges “totally baseless” and a ploy by plaintiff’s attorneys.

“The worst thing was the denial in the face of obvious evidence of undue influence,” Praglin added. “The caution I’d give anybody involved in public health is that when you look at science, you have to ask who wrote and funded the studies being used. If it’s all being written by industry hired guns, they are out to save a buck for the companies.”

In the meantime, one of the nation’s premier cancer research labs, the National Toxicology Program, has been studying the effects of chromium 6, but won’t have results for at least another year, possibly two.

Even so, there remains no firm number to indicate at what level chromium 6 poses a health risk to humans, if at all, a reality that Schiff calls “disappointing.”

“Time is not our friend with this,” concluded Schiff. He has acquired $1.5 million in federal funds for a chromium 6 filtration system; the cities must contribute some matching costs. “The plume is moving and threatens the water supply. If this turns out to a be a cancer-causing chemical, it poses a significant threat.”

Copyright Chip Jacobs

Related Posts

The Brown Air Prequel for our Climate Change World

Why the Sky Disappeared, and Why L.A.'s Smog-Choked…

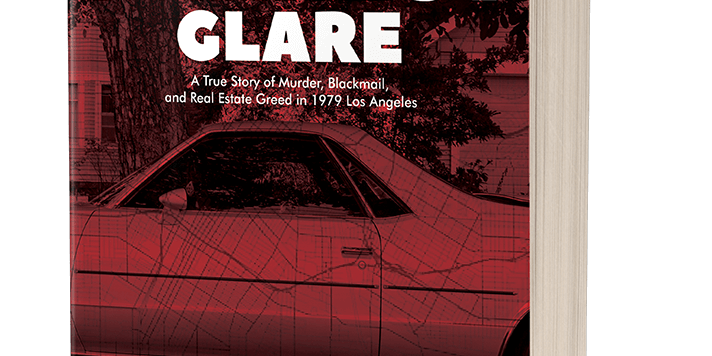

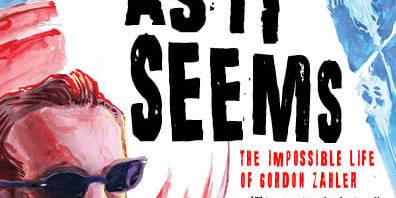

At Christmas, “It’s A Wonderful Life.” In 2022, hopefully it’ll be a series about a life as Impossible as it is Strange!

Mercury Media has optioned its inaugural title, the…