Square-jawed and persuasive, developer E.C. Webster, it was said, could’ve sold plots on Mars for a profit. Luckily there was Pasadena of the late-1880s, where Webster’s knack for acquiring properties at “shoestring prices” before reselling them for nifty gains made him a legend.

The dealmaker behind the Hotel Green, the Grand Opera House, and Raymond Avenue’s opening typified a boomtown spirit champing to wring fortunes from the land. And what a spirit it was. Between 1886-1887, a foothill plain known for citrus groves, sheep pastures, and a single saloon transformed into, arguably, one of the hottest real estate markets in America.

Pasadena’s founding fathers in the “Indiana Colony,” who a decade earlier had espoused equitable property division among its members, surely cringed at the frenzied activity. If you had cash, you were cajoled to invest. If you owned a tract, you were wooed (or badgered) to subdivide.

Take the case of O.H. Conger, who accepted a syndicate’s $15,000 offer (about $406,000 today) for his twenty-acre orchard south of Colorado Street in this period. He netted a $5,000 windfall. Craving more, the buyers held an auction they marketed with free train rides, complimentary grub, and a brass band. Though some deemed the event indecorous, seventy-seven of the eighty-seven lots divvied up from Conger’s property sold for a collective $22,000.

The county recorder’s office illustrated this was no fluke. During the “great” land rush, Los Angeles, then twelve-times larger in population, filed 549 subdivision maps. The future home of the Rose Parade submitted seven times more.

Speculators, or “boomers” as were tabbed, seemingly crept everywhere in a town still lacking a charter, reliable water system, or decent bridge across the Arroyo Seco. They and the fifty-three local real estate agencies brokered transactions in Victorian-age offices and on plain sidewalks. They shadowed rivals doing site tours to swoop in once they left. They pounded on homeowners’ doors at midnight dangling can’t-miss sales-contracts. They twisted fancy moustaches, soliciting clients with fountain pens and promises.

Conservative financiers fretted the real estate bubble would burst, but it wasn’t a universal opinion. As the Valley Union wrote with a racial tweak: “Put your money to soak in real estate rather than in a Chinese washhouse.”

Many heeded that siren of temptation. A landowner pestered to sell five acres he purchased in 1881 for $2,000 eventually acquiesced to chop up his parcel. He turned a sixty-fold profit. In another case, a lot at Marengo Avenue and Colorado Street where the First Methodist Church once stood became—what else—a residential subdivision.

One evening, a druggist was compounding medication with a mortar when speculator Johnny Mills rushed into his pharmacy. In his hand was a map displaying a plot that he urged his would-be client to snap up before other bidders the next day. The preoccupied druggist refused to glance at the document, so Mills gestured to a jingling streetcar outside waiting for him to say final chance.

Five minutes later they had an agreement. Shortly after that, Mills represented the pharmacist reselling the plot in a classic flip you’d see today on HGTV.

All told, twelve millions dollars ($324 million now) in deals were transacted in 1887. Weed-strewn lots, forlorn houses, vine-covered bungalows; crumbling shacks—all what mattered was their future worth! Why not, when a $300 parcel on Fair Oaks two years later fetched $10,000?

Years before Old Money Pasadena crystallized on Orange Grove’s Millionaire Row, the nouveau riche lived high on the proverbial hog. Men booked hotels for boozy stag parties and poker games. Others flashed diamonds, rode in fine buggies, and ditched nickel cigars for gold-banded ones.

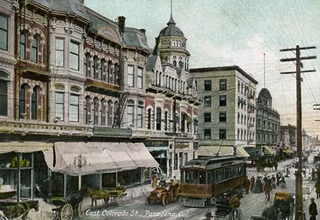

Amid the feverish wheeling and dealing, bigger investors jumped in ways that expanded Pasadena’s reach. An electric light and power company hung out a shingle. Developments on new streets—Los Robles, El Molino, and Lake avenues— pushed activity eastward. Colorado Street underwent a partial street paving, and welcomed the new Arcade building and fresh shops. To keep pace will all the building, a dirt-streaked tent city to shelter workers popped up in what’s now Central Park.

Then, as quickly as it started, the law of economics prevailed once the market bottomed out. Sellers now dwarfed buyers. Commercial lending slowed to a trickle. Auctions proved duds. Before long, some of those high-flying speculators vanished (probably with investors’ money). One hustler who’d made six figures in real estate resorted to selling peanuts on trains for his keep. Another drove a mule pulling a streetcar.

The way amateur historian J.W. Wood saw it, “The paper fortunes, and some more substantial, had collapsed with amazing celerity, and the dazed and sickened boomers’ dream was over!”

Pasadena’s future might’ve tanked, too, if the banks, whose net assets had plunged by two-thirds, didn’t grant loan-repayment extensions, or aid customers staving off bankruptcy. The population nosedived anyway, as people left behind their failures, only resurging in the next century.

As for E.C. Webster, Wood reported he abandoned his “castles in the air” for a docile life in Missouri.

Unless indicated, monetary figures were not adjusted for inflation.