We had the good fortune of connecting with Chip Jacobs and we’ve shared our conversation below.

Hi Chip, why did you decide to pursue a creative path?

Hi Chip, why did you decide to pursue a creative path?

In fall 1982, at parents’ night at my college fraternity, I dropped a bomb on my father, telling him that I was switching my major from business administration to journalism. He’d been a child of the Great Depression, having me in his mid-forties, and ever since disdained newspaper reporters as sort of bottom-scrapers who recorded the day’s big events rather than contributing to society writ large. The argument that erupted between us that evening felt like the climax of a John Hughes coming-of-age movie. Suddenly, a 100+ people listening to a speaker up front swiveled their heads to the back of the meeting hall to hear me scream that this was MY damn life, not his to plot out; that my heart would never be in a soulless corporate job, let alone the slow-suicide of working in family real estate business, however much it’d paid my way. We were a couple of distant planets afterwards, him furious, me terrified about the ramifications of my ill-timed declaration of independence. Somehow, we remained on speaking terms.

By 1990, after flirting with the idea of a career as CIA analyst (you know, to save the world from nuclear apocalypse), I secured my first reporting job at the Los Angeles Business Journal. Never was I happier. It wed my natural, admittedly annoying curiosity with a genuine love of writing, filling me with pride and a hunger to improve every day. Seven years, and a bunch of newspaper posts later, I took another plunge you could either term courageous or self-sabotaging. On a decided roll, with the Los Angeles Times interested in hiring me after a string of front-page exposes, I up and quit its fierce rival, the Los Angeles Daily News, to pen my first book, Strange As It Seems. My editor and others begged me not to, that I was making a terrible mistake, but hazy voices seemed to be calling me. My mother’s side of the family, I knew by then, was chalked with creatives. There was that famous European dancer, a Broadway star, Hollywood directors and musicians; heck, author Irving Stone was a distant cousin.

Still, in leaving a job I adored for this more solitary pursuit, I frequently second guessed my decision to walk away from the never-dull newsroom. When a  preliminary book deal with St. Martin’s Press fizzled, it seemed as though I’d magically converted that potential folks told me I had into smoking ruin. My second book about the “Great” L.A. smog crisis garnered critical acclaim, though releasing it at the onset of the “Great Recession” was a recipe for commercial frustration. I plowed ahead after Smogtown anyway, reminding myself about all those moody writers sustaining themselves on little more than self-belief while peers racked up champagne successes. In reporting, I always felt luck sided with me. In the literary universe subject to fads and social changes, it was swamp-plodding. One day, when I was actively considering returning to journalism, an epiphany floated down on me. I was picking book subjects that in a fashion picked me based on my childhood, my outrage as the world as it was, or on topics that’d always secretly fascinated me. My mom, who passed on in 2008, just as my biography about her larger-than-life brother was slated to appear, had always encouraged me to lean into my artistic ancestry. Sometimes I loved her for that, though other times I resented it for where it lead me

preliminary book deal with St. Martin’s Press fizzled, it seemed as though I’d magically converted that potential folks told me I had into smoking ruin. My second book about the “Great” L.A. smog crisis garnered critical acclaim, though releasing it at the onset of the “Great Recession” was a recipe for commercial frustration. I plowed ahead after Smogtown anyway, reminding myself about all those moody writers sustaining themselves on little more than self-belief while peers racked up champagne successes. In reporting, I always felt luck sided with me. In the literary universe subject to fads and social changes, it was swamp-plodding. One day, when I was actively considering returning to journalism, an epiphany floated down on me. I was picking book subjects that in a fashion picked me based on my childhood, my outrage as the world as it was, or on topics that’d always secretly fascinated me. My mom, who passed on in 2008, just as my biography about her larger-than-life brother was slated to appear, had always encouraged me to lean into my artistic ancestry. Sometimes I loved her for that, though other times I resented it for where it lead me

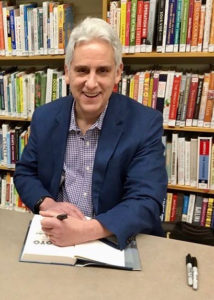

I gulped reliving those memories when Arroyo, my debut novel about Progressive-Age Pasadena and its mysterious Colorado Street Bridge came out, reaching, to my surprise, the L.A. Times bestseller list and becoming a local hit. As I reflected on my serpentine journey to that pre-pandemic jubilation, I prayed that the father who wanted me to grip a briefcase instead of banging away on a keyboard was peering down from the afterlife. Hopefully, he appreciated that our Reagan-era hollering match funneled me into the Chip I had no choice in becoming.

Let’s talk shop? Tell us more about your career, what can you share with our community?

When I was a kid in the foothills of Pasadena, I had this older, neighborhood pal blessed with the innate ability to sketch. Football players; cats dressed up like NHL players; smoggy landscapes. Gerald just had the gift. I tried copying him, and quickly realized I was no Gerald, for I topped out artistically with stick figures. Reading was where I found my organic meter: ”The Three Musketeers,” “Robinson Crusoe,” and “Lord of the Rings” transported to me to the most fanciful spot in the universe: between my own ears.

By college, the verdict was in. I should stay a million miles away from advanced mathematics (and drawing for that matter) and apply myself in any field where the ability to tell stories was at a premium. And who was I to argue with a metaphorical jury? The first time I saw my byline was in a political column at my college newspaper, The Daily Trojan. I grabbed every copy I could find, feeling the rock star when classmates gave me the occasional attaboy. My roommate started calling me “Scoop.” I was giddy. And just as naive.

Thousands of newspaper articles later, on subjects ranging from the genesis of the Original Tommy’s hamburger empire to an investigative take-out about a genius environmental businesswoman who ran with shadowy CIA types, I know I stayed in the profession I was supposed to, even if often paid like crap and some of my subjects pined to get me fired. Here’s the thing: every word one writes is one’s own mirror on the world—a reflection of not just dry facts and curated quotes but the writer’s life experiences. My articles were also my Killroy: proof that I was here. They painted heroes, identified villains, and, I hope, gave folks blue about their lives an occaionsal chance to laugh. Only this Chip would be weird enough to jump at the opportunity to write about the joys of dumpster diving. All those years removed from USC, I wouldn’t have it any other way! Journalism for me was less an occupation and more a crusade. From my first reading of All the President’s Men, I was hooked. Woodward and Bernstein became my Lennon and McCartney.

Thousands of newspaper articles later, on subjects ranging from the genesis of the Original Tommy’s hamburger empire to an investigative take-out about a genius environmental businesswoman who ran with shadowy CIA types, I know I stayed in the profession I was supposed to, even if often paid like crap and some of my subjects pined to get me fired. Here’s the thing: every word one writes is one’s own mirror on the world—a reflection of not just dry facts and curated quotes but the writer’s life experiences. My articles were also my Killroy: proof that I was here. They painted heroes, identified villains, and, I hope, gave folks blue about their lives an occaionsal chance to laugh. Only this Chip would be weird enough to jump at the opportunity to write about the joys of dumpster diving. All those years removed from USC, I wouldn’t have it any other way! Journalism for me was less an occupation and more a crusade. From my first reading of All the President’s Men, I was hooked. Woodward and Bernstein became my Lennon and McCartney.

Transitioning to being an author prone to skipping around in different genres requires many of the same traits: confidence, creativity, a bit of insanity, and a lot of sheer “want-to.” Many assume being an artist is about creating something thought-provoking that you gawk at in art galleries or murmur about on in view of catwalk or book signings. After many years, I view it differently. I believe it’s about challenging oneself to stretch higher than ever imagined, and knowing the result is for both other people’s benefit as well as leaving footprints that our souls recognize as evidence of right-brained free will.

Let’s say your best friend was visiting the area and you wanted to show them the best time ever. Where would you take them? Give us a little itinerary – say it was a week long trip, where would you eat, drink, visit, hang out, etc.

It’s an autumn Friday night, and we’ve been starving ourselves for a gluttonous weekend. Dinner has to be at Park’s (Korean) BBQ, on Vermont Avenue in mid city LA. Come for the grilled meats, stay for the kimchi and pork belly. Did I mention beer was created thousands of years ago specifically for this salty fare?

The following morning is no time for slacking or calorie counting. It’s breakfast at South Pasadena’s retro-roofed Shakers, crispy hash brown, please, and then a drive down the Harbor Freeway to the gray lady — the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum — to watch my beloved USC Trojans play on that immaculate green turf, as I’ve been doing since I was a child barely able to see anything. Since man doesn’t live on Coliseum dogs alone, it’s Langer’s No. 19 pastrami for a post-game meal. Back home, we fall into the kind of slumbers reserved for pythons after consuming a gazelle.

Sunday, we eat lighter, maybe something from a San Gabriel Valley farmer’s market. Next, my guest allows me to give them a tour of my hometown, just like  my protagonist Nick Chance in my novel Arroyo. We drive up into the San Gabriel Mountains to see where Thaddeus Lowe’s once world-famous electric railway ran, then walk off some fat by hiking south from the Rose Bowl to where dreamy Busch Gardens and exotic Cawston Ostrich Fam used to sit. Since I can only describe its paintings so well, we venture into the Norton Simon museum for glimpses of the world’s most prize art, from Picasso to you name it . After that, we traipse around Caltech’s shady campus, home of eggheads, Nobel prize winners, and underrated architecture. That night, we’re back on the road, grabbing Ethiopian food (literally with our fingers) at Massob, capped by an intimate show at The Mint LA club. If we’re lucky, we’ll see an enormous talent, like Squeeze’s Glenn Tilbrook, blow the doors off the place. If not, we’ll see a Donovan impersonator (kidding).

my protagonist Nick Chance in my novel Arroyo. We drive up into the San Gabriel Mountains to see where Thaddeus Lowe’s once world-famous electric railway ran, then walk off some fat by hiking south from the Rose Bowl to where dreamy Busch Gardens and exotic Cawston Ostrich Fam used to sit. Since I can only describe its paintings so well, we venture into the Norton Simon museum for glimpses of the world’s most prize art, from Picasso to you name it . After that, we traipse around Caltech’s shady campus, home of eggheads, Nobel prize winners, and underrated architecture. That night, we’re back on the road, grabbing Ethiopian food (literally with our fingers) at Massob, capped by an intimate show at The Mint LA club. If we’re lucky, we’ll see an enormous talent, like Squeeze’s Glenn Tilbrook, blow the doors off the place. If not, we’ll see a Donovan impersonator (kidding).

Come Monday, we get tacos to go from Lupita’s, a strip-mal eatery close to a dog-washing shop, and eat lunch on one of those flyover benches carved inside the historic, Arroyo-Seco-spanning Colorado Street Bridge. The mountain views there are heavenly. Given our fare over the last three days, we might just ascend up those Pearly Gates, grateful to have been alive and hopeful for a return.

The Shoutout series is all about recognizing that our success and where we are in life is at least somewhat thanks to the efforts, support, mentorship, love and encouragement of others. So is there someone that you want to dedicate your shoutout to?

I’d be nowhere, obviously, without the undying belief of my family, friends, work colleagues, plus the tail-wagging support of the mutts I’ve loved. When your dog stares you in the eye, telegraphing a message that he/she knows you can do better than you are, you disregard at your own peril.

High school — in my case, Flintridge Preparatory School just about JPL in La Canada-Flintridge — was where I first discovered my footing for the future. Our history teacher there, John Hamilton, was a brilliant communicator who knew how to breath the past back to life for us bunch of distracted, girl-crazy boys. How? He framed personalities, conflicts, and giant stakes into a narrative that made you hang on his every word. To him, manifest destiny wasn’t only an expression of America’s westward pioneers. It was what lived in each one of us to do whatever it took to extract what we had to offer the world, or die trying. My senior year English teacher, Cheryl Ginzton, was another shaper of me. I still remember vigorously arguing with her about Hamlet’s sanity, and her later urging me to be a writer who followed his curiosity wherever it transported him. Though Mr. Hamilton is no longer with us, my English teacher is. I know that because when I did a book reading at the Pasadena Central Library, she showed up with a copy. Sure, she dozed off while I was reading from my novel, but I was humbled she made it. Plus I will parlay the scene, names changed of course, in a future book fueled by my unquenchable, sometimes pathological need to tell stories.

The contents of this post are nearly identical to the article that ran in Shoutout LA

Related Posts

The Tree and the Voice and Writing a Novel

"Later Days" began when a brilliant, dying friend asked me…

From the Department of Unexpected: “Later Days” Wins General Fiction Prize at the American Writing Awards!

And, in another humbling development, it was also named…

“The Lost Art of Album Release Parties” – Boomer magazine

We hustled into my room, nodding at the familiar, Jimmy…