More times than he can count, Daniel Arguello has begun his day massaging his achy right leg, the one ripped to pulp in Vietnam 37 years ago, and doing what others might judge absurd. He thanks it for courage in life’s darker moments.

When at 18 he overheard an Army nurse poormouth his chances to walk again, the high-school dropout from East Los Angeles grunted and grimaced through a long rehab until he actually could jog without wishing someone would put him out of his misery. The comeback power of that rebuilt limb later steadied him through a job market that distrusted his skin color, then the psychic wreckage of burying a son.

It even withstood the backlash of helping nail one of Alhambra’s favorite sons at the same juncture Arguello’s foes were assailing his scruples. Freakish timing or mere payback, he would never be the same.

Ever since August 2004, when he wore a secret recording device that county prosecutors used to indict former councilman and school board member Parker Williams in a money-for-vote sting operation, creepy things had been happening to the then-vice mayor. Strangers had popped up at City Hall and his favorite Pasadena lunch spot inquiring about Arguello’s whereabouts. Anonymous calls to his lawyer had warned that, “Dan should be very, very careful.” Those unsolved incidents and a few others brought him police protection.

Late one Tuesday evening this spring, outside one of the Main Street clubs he frequents, Arguello, 58, sensed eyes tracking him again. Was it intimidation? Was it someone looking for dirt to smear his credibility as star witness in the Williams trial?

Whatever it was, Arguello decided he was done peering into the shadows. So he leaned on that gimpy leg once more, walking home on it for a mile, instead of driving his orange Saab. Paging Oliver Stone.

“I’d lived worried long enough” Arguello said. “I was fed up. I was thinking that night, ‘If you’re following me, come and get it!’ So I walked … Not that I’m fast.”

‘Politics is a battle’

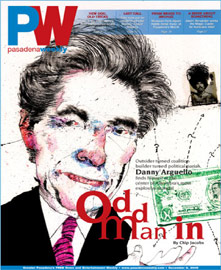

Overtaking him certainly is easier than pigeonholing him as a deserving martyr or crafty opportunist. After two terms on the Council, Arguello has no signature policy that jumps out, and little statewide cachet. His top achievement may be prodding a city Establishment known for ferociously protecting its own.

Trim and single, with feathery salt-and-pepper hair that draws comparisons to “a Latino Richard Gere,” Arguello has a playboy reputation that he know irks his more straitlaced enemies. He admits doing his best thinking in the wee hours with a scotch in hand and Miles Davis on the stereo. Affable and droll, popular with shopkeepers and gadflies, he also is a book hound with a passion for British literature.

None of which says much about the sunny fatalism washing through a guy who seems to tread cautiously around destiny’s cliffs without canceling the hike.

“Some people say I still have a Cholo gait. They say, ‘Get a haircut and a better walk!’ What they don’t know is that I keep my hair long because half my peers have lost theirs. What they don’t know is that I walk like this to cover up my limp.”

Don’t expect his council colleagues to lend him a cane. While tempers have cooled between their respective factions, 2006 may prove explosive. The District Attorney’s case against Williams could peel back how small, land-oriented cities like Alhambra truly operate, and what money can buy if a familiar figure serves it up.

“I know who Parker is – I don’t think there’s anybody who hasn’t been touched by the good things he’s done,” current Mayor Steve Placido said. “So to see someone or two people involved in bribery, I don’t think that casts a favorable light on the city. Unfortunately, the facts that we know are mostly through the papers, and I’m not sure the papers knows that much.”

Williams, 68, a gaunt-faced man respected for his decades of civic involvement, declined comment for this story. Since his indictment, he has remained visible around town, telling friends he made a stupid mistake, one source said. Indicted with him was Frank Liu, 72, his business partner on the senior-housing project that Williams allegedly offered $2,500, then $25,000 to Arguello to support.

Richard Hirsh, Williams’ defense attorney, would not discuss strategy except to say that Arguello’s “character” would be an issue at trial. No date has been set.

What likely motivated Hirsh’s client? Leverage.

Last spring, Arguello nearly accomplished what no one else ever had in this city pinched between the San Gabriel Mountains and the Valley’s southern rim. He nearly toppled Alhambra’s white Council majority with his own Latino clique after the city’s most legendary Anglo councilman, Talmadge Burke, died.

The irony was undeniable, the bigger metaphor obvious. It would happen in Los Angeles with Antonio Villaraigosa’s milestone 2005 mayoral election as it already happened here. Latinos whose ancestors once hoed the fields wanted a place at the table. Arguello likened it to India rising up against its “British Viceroys.”

Williams, however, wasn’t as much interested in history as he was in counting council votes — three out of five being the magic number — for his city-subsidized development. Too bad he didn’t wait until after the November 2004 election, a mudslinging contest that seemed more like a big-money congressional race than small-town campaigning.

Arguello, first elected in 1998 and re-elected in 2002, wasn’t running himself, but his influence was, and it got walloped. His entire slate of council and school board candidates all went down in flames to Establishment-backed figures.

The reconstituted council majority, quarterbacked by the clean-cut and cunning Paul Talbot, pounced vengefully. It took away the Buick LeSabre that Arguello was allowed to use in his rotation as mayor amid uninvestigated charges that he drove it to strip clubs and bars. His plum committee posts were yanked next.

The venom usually did not cascade out at council meetings; that was left for the insanity of election season, or whispers to reporters or in private tirades. But if you watched closely, the desired impression that all-was-well was purely cosmetic.

At one tense council meeting, Arguello challenged the community activist who accused him of misusing the city car to show his evidence. There was silence.

Rene Nava, a onetime Arguello supporter, wasn’t as quiet when he ran against him. He denounced Arguello for dirty campaigning after Arguello accused him of stalking a woman. The messy charges hit the papers, and later the legal docket.

Can’t you feel the love?

“Before Dan Arguello came along, there never was hardball politics here,” Talbot, 44, remarked. “It was much more collegial. Dan’s style is old school LA where you fought for every inch of ground. We had a team-building session in January where Dan said, ‘Politics is a battle.’ We said, ‘No, it’s community service.’”

Community, as you’ll see, is a rather elastic term in Alhambra.

Now on the losing end of a 4-1 majority, Arguello has had a simple enough objective – staying relevant. He shows up to meetings often as the least liked fellow in the room. He plays soft-voiced devil’s advocate when there’s an opening. He birddogs officials he contends are “fast tracking” the $400 million redevelopment juggernaut that spruced up downtown and is now heading west.

Probably not surprisingly, Arguello himself wants to head north. Last month, he announced his second bid for the state Assembly seat occupied by fellow Democrat Judy Chu. Arguello said he’s not so much fleeing his hometown as he is chasing Sacramento in his longtime quest to be a state lawmaker. The folks who hope he stumbles to a better-funded opponent chirp that Arguello better not act as if his council job is “the consolation prize” if he loses the race for the 49th district.

Still, it was Williams, the former Chamber of Commerce president known for his workout fanaticism and general exuberance, who sullied Alhambra’s good name, right?

You might not know it from Alhambra’s leadership, which never publicly denounced his alleged graft. Some leaders, in fact, privately suggest that Arguello was so inherently venal that he practically emailed Williams he was for sale.

Bureaucrats don’t seem to be sweating the headlines, either. This fall, the Williams-Liu project was forwarded to Alhambra’s planning commission for consideration before Arguello’s appointees on the panel tossed it. The development now sits in limbo.

City Manager Julio Fuentes, who declined comment for this story, said in a statement the city had “no authority” to halt a project review if the applicant had submitted the proper paperwork and fees. The neighboring city of Montebello took a different tact after Williams and Liu were arrested: they scrubbed a condominium project they were proposing.

Then again, there’s no place like Alhambra.

Powerful friends

The bedroom community of 86,000 has your standard-issue car dealerships, dated neighborhoods, and institutional stucco. It’s redeveloped downtown, a compact version of Old Pasadena fringed with clubs, art-deco neon and ethnic beauty shops, teems on weekends. The $25-million facelift there looks like money well spent.

Yet reputations, as Arguello will remind you, can be hard to shake. Eccentric music producer Phil Spector, now on trial for the 2003 shooting death of an actress at his Alhambra mansion, once commented, somewhat quizzically, that his adopted city, “is a hick town where there is no place to go that you shouldn’t.”

At 102 years old, Alhambra is one of the region’s municipal old-timers. This longevity, observers suggest, has accounted for a virtually permanent white incumbency on the council, even as its constituency became minority-majority. Alhambra was once fairly split among white families with generational roots here and Latino empty-nesters who relocated from East L.A.

Today, Asians, particularly immigrants from China and the poorer Far East nations, comprise nearly half the population. Latinos represent about one-third. Whites make up most of the dwindling balance. No Chinese-American has ever been on the council, though Japanese-American Gary Yamauchi was elected last year.

All this, however, was static in the Shakespearean-like melodrama in which somebody as controversial as Dan Arguello tried outlasting somebody as entrenched as Parker Williams.

If the paradox doesn’t wow you, the trampled friendships may. The same people who today wince at Arguello’s name are precisely the ones who groomed him for office.

In 1998, he was a comer: a self-deprecating moderate with a Purple Heart, an easy smile and a living room everybody who mattered had stood in.

Talbot, who runs a State Farm Insurance agency with his wife, not only re-named Arguello to a commission post that Arguello used to create a following, he also raised campaign money for him — and, of course, insured him personally. School Board Member and ex-councilwoman Barbara Messina, now one of Arguello’s most braying critics, dished out counsel. Typical of small towns, their kids were friends.

These insiders had something else in common: real estate. It’s been the coin of the realm here since Benjamin Wilson, the city’s founder, settled a farming empire stretching from Riverside to the Westside 20 years before the Civil War.

That tradition lived on. Williams, once in recycling and economic development, jumped into developing. Talbot owned a piece of a First Street business a few blocks from the $20-million Edward Cinema complex downtown. Councilman Mark Paulson, a career realtor, managed and rented property nearby. Even one of the city’s famous old police chiefs was an ex-real estate man.

It gets better. Paulson sold Williams and Liu the land they needed for their now-infamous housing project. Before that, Paulson sold Arguello the right house for launching his campaign.

Given those strands, few were prepared when Arguello and fellow Councilman Efron Moreno started poking into city contracts and practices. Why, they asked, did Alhambra’s longtime outside law firm, Burke Williams & Sorenson, never have to bid? The firm has netted $8.8 million from Alhambra in the last five years.

The chasm among former friends cracked wide in 2003, when Talbot proposed election changes that would have limited individual contributions to $2,500 and created a runoff system. He said it was fairness. Moreno and Arguello labeled it an Establishment power grab fueled partly by anti-Hispanic prejudices.

“I came on here because I wanted a change,” Moreno, 39, said. “I didn’t like this good old boy thing where the machine expects you to pay your dues through the chamber, the Rotary Club and so forth. … I remember asking [Talbot] why he was not supporting Dan in his last reelection. He said, ‘I’m afraid you’re [also] secretly supporting a Hispanic woman candidate and somehow the three of you will get along better and fire the city manager and the city attorney and you’ll turn Alhambra into South Gate.’ It was like, man, how dare you?”

South Gate is anathema around municipal water-coolers these days. The small community outside downtown L.A. nearly went bankrupt after its former city manager, Albert Robles, was convicted of bribery in a case that cost taxpayers $12 million.

Talbot disputed using the word “Hispanic” in his conversation with Moreno. He also asked how he could hold a racial grudge when a slew of city staffers, including the long-serving Fuentes, are of Mexican descent. So are two candidates he endorsed last year.

“My comment about South Gate was not about race. It was about cronyism” by Arguello’s camp, he said. “I’m a Eucharistic minister giving people communion and I know people in the church have read quotes that I’m racist. It’s painful. In America, nothing is worse than being stamped a child molester or a racist.”

Because of that and other discord, Talbot said that while he remains cordial to Arguello, “there is no real relationship.”

You gotta wonder

Alhambra’s old guard was strafed in the weeks leading up to the November 2004 election by a Moreno mailer titled “The Greedy Bunch.” It took swipes at the likes of Williams, Messina and then-Alhambra Education Foundation president Steve Perry. Perry, a former city police officer and school board member, was fired from both jobs after getting caught stealing $30,000 from the city’s police association when he was in charge of it in 1992.

“These,” Moreno said, “are the people running the city.”

The Establishment answered. Rumors floated that Moreno was tied to the Mexican Mafia. He’d lose in a tight race.

Doubts also wrapped around Arguello, an auditor at Pacifica Services, a connected Pasadena-based project-management and consulting firm. A buzz grew that he had steered a towing, golf course, lobbying, and other contracts to associates from “East LA.” This was thinly veiled code for the perceived Latino political mob run by former lawmaker and onetime-Arguello boss Richard Alatorre.

Around City Hall, acquaintances that showed up seeking work were caustically dubbed FOD (“Friends of Dan”). Interestingly, most of the work they received passed on 5-0 council votes with little debate. Only the golf course deal to George Almeida was rescinded for slipshod performance.

“Dan’s priorities were not to advance the priorities of Alhambra but to advance those of Dan Arguello,” said Barbara Messina, whose husband was defeated by him in the 2002 election. “I’ve talked to people who knew him before I knew him and they confirmed that this is the way Dan is. He’s ruthless… Yes, he can be very smooth … But if their faction would’ve picked up one more vote, the city would have turned into something really ugly.”

Arguello acknowledges urging associates to bid in every case except the towing job, saying public contracts should be open to the general community. He believes the patronage charge hit because an “inner circle” was used to getting city work, and because he wanted a robust debate on issues, not “lovefest” rubber-stamping.

“I never told anybody they’d get a contract,” he said. “I encouraged them to compete. Contract compliance is what I do for a living. I know the law.”

Arguello’s son, Dominic, said the rancor toward his father, the perception he’s dirty or over blew the threats against him to garner sympathy, should be discounted because they were kicked up “the same group.”

“Anybody who knows my father knows the person he is,” he said. “He’s a man of his word.”

Then there’s the Alatorre factor.

Before he went to the LA City Council in 1985 as a raspy-voiced backroom fighter, before he pled guilty to accepting illicit funds in a scandal that also exposed a cocaine addiction, he was Alhambra’s popular state assemblyman. Even after his conviction, he was so well regarded that Burke William hired him — on Arguello’s recommendation — for $50,000 to advise the city on litigation aimed at completing the long-delayed 710-Freeway extension. Rock-ribbed support for the roadway is ideological sacrament here.

Yet in 2002, Alatorre watched his name trashed in order to club Arguello.

“My observation, and I am on the outside looking in, is that Alhambra has been a very entrenched city led by a handful of people and that anybody who wants to challenge that becomes an enemy,” Alatorre said. “They should give Dan credit for being honest, but sometimes you wonder who was offered the bribe.”

Through the pain

The man in the middle stabs gingerly at his Caesar Salad as he retells the prophecy.

It was just after his triumphant reelection in 2002, and the iconic Talmadge Burke was congratulating him. Burke, for those who’ve lived out of the country, was Alhambra’s 13-time councilman. With 51 years in office, he was California’s longest-serving elected official, a legend who fought the railroads and remembered the old smudge pots, not to mention being a property owner himself. Well-wishers lavished him with endless parties and 20-plus buildings in his name. When he died in February 2004 in his mid-eighties, the town lost its eternal godfather.

But back in 2002, Burke, a lifelong Republican, had a story for Arguello. It was how Alhambra’s Establishment guarded the kingdom. When 1970s-era Councilman Mike Rubino tried shaking down an ambulance company operator, the city elders, Burke said, made sure the person he sought the bribe from was an undercover police officer. Rubino was prosecuted for his act and was forced to resign in the end.

“Talmadge basically warned me,” Arguello said with a nervous smile. “Eighteen months later, it came true. Paul Talbot had done such a good job telling the old Establishment that I was sleazebag that people started believing it. The Pasadena Star-News wrote about me and the towing contract. People started believing the myth, and Parker was one of them.”

If you could skip back in time, it’s miraculous Arguello was around to hear that tale.

He was raised in the east L.A. neighborhood of Boyle Heights to working-class parents that he joked didn’t “beat him enough” because he turned out so levelheaded. Needing pocket money, he worked as a busboy and as a milkman. Those graveyard shifts crimped his senior-year studies at Roosevelt High School and he dropped out.

Eddie Martinez, one of Arguello’s commission appointees, grew up next door. The teenage-Dan he remembers was not a rabble-rouser screaming, “Viva La raza!”

“He was [just] self confident and good with the girls,” Martinez said.

Then he was drafted.

The Army welcomed recruits, Arguello recalled, with a “lousy” steak sandwich at its Olympic Boulevard induction center before busing them to Fort Ord, near Monterey, for basic training. In Louisiana, where Arguello completed his infantry training, he learned to sidestep armadillos and coral snakes as he would Jim Crow attitudes risky for an olive-skinned recruit with black friends.

It would get scarier. On his helicopter ride into Vietnam, Arguello gazed down on a magnificent countryside he instinctually knew America (and him) didn’t belong. The Army stationed him with the 25th Infantry near Cuchi. Just a city kid in 1966, he barely realized the marches he was on were patrols to flush out the Viet Cong.

He felt safer when his platoon was attached to a mechanized unit. One night, though, while dozing on an armored personnel carrier, the quiet exploded with artillery and tracer bursts. His platoon had been lulled into a trap.

Boom!

“I remember being in the air and everything looking all red,” he said. “Next I was on the ground, scrambling for my weapon, and I couldn’t see out of one eye. I couldn’t feel one of my boots, either. It’d been blown off my foot.”

A Puerto Rican platoon buddy tried staunching the bleeding, but where to start? Arguello had nine acute shrapnel wounds lacing him scalp to feet.

Medics ferried him to a field hospital. A military priest came to his bedside within an hour and dispensed Last Rites. Somehow, despite the blood loss and trauma, he hung on, “fickle Catholic” that he was.

They transported him to Saigon for surgery, then to Japan for skin grafts. It was there he heard a nurse remark he was being shipped home because he’d never walk on his right leg again. From Japan he went to Walter Reed Hospital, and from Walter Reed to the West Coast for painful rehabilitation next to vets who had lost eyes, legs and arms.

“I had to live with this — seeing people missing body parts — for a year. Though I came back with a lot intact, I still lost parts, too.

“The fear of not being able to make my dreams pushed me. Small dreams: walk on two legs again, go to college. If I didn’t overcome my fear, I didn’t get to reach my dreams. My right leg taught me that.”

The Army assigned him a grunt job at a Ford Ord weapons warehouse to finish out his tour of duty. Instead of breezing through it, he found himself facing military investigators accusing him of filching a .45-caliber handgun, purportedly to show off to chums back home. They confined him to base and assigned him a hack lawyer with a miniature hangman’s noose on his desk. Arguello, then 19, maintained his innocence and snuck back to LA on weekends.

“My parents didn’t’ know about the charge,” Arguello said. “They thought I had a weekend pass. The Army was screwing me over.”

Right before his tour ended in June 1968, investigators cleared Arguello. The culprit had been his drill sergeant.

Bread with your soul?

More than thirty years removed from those painful memories, Arguello tried acting unfazed when Williams strode in, but his heart was pounding out of his chest. Over chicken lunches, Arguello got him to lay out the bribe, just as the D.A. instructed.

There was a dreamlike quality about it all.

Once Arguello and Williams finished their meals, they headed toward their cars for the money drop. At his Honda SUV, Williams reached in, pulled out an envelope containing $25,000 – ten times the previous amount — and handed it to Arguello.

This time, deputized by the D.A., Arguello accepted it. Arguello, a believer in destiny, said he had to do what was right, whatever the Establishment thought of him playing the bait.

“At that point, I wasn’t looking at what was going to happen or what people would say, because of my fear and respect of the law,” he said.

“The whole thing was still like a bad movie.”

At least he had his legs to boost him home.

* * *

The Los Angeles County District Attorney secretly recorded the following conversations in a summer 2004 sting operation to expose a money-for votes scheme in Alhambra. It began when developer Parker Williams allegedly offered Councilman Daniel Arguello $2,500 to support a senior-housing project.

August 16 phone call:

Williams: “I’d he happy to give this to your closest friend. You’re concerned that I may be the enemy, and I can assure you that I am not … There will not be a breath of this anywhere, ever … I have always done exactly what I say I’ll do. I want you to understand clearly, uhh, there will be no backwash from this. None …So you get another day or two, think about it and figure out a way that it’s absolutely comfortable for you …”

August 18 phone call:

Williams: “Listen here …you must have decided that I can keep my mouth shut, or you wouldn’t be saying okay to this … This is a difficult decision … And I make it difficult because I want to do the, uhh, I can’t write thousand dollar checks. I don’t have 25 friends to do that with and for, (if) you know what I mean?”

Arguello: “Yeah, I understand, Parker.”

Williams: “This is easier for me. It gets the job done … And (whether) you use it for campaign (purposes) or you use it for tuition, it doesn’t make a damn to me.”

Arguello suggested they meet at Starbucks on Main Street in downtown Alhambra.

Williams: “Well, if I’m gonna meet you somewhere at 12:30, you outta buy me lunch.”

Arguello: “Okay, I’ll buy you lunch.”

The two picked Charlie Trio’s Italian restaurant across from Starbucks.

Williams: “Do you mind if we’re seen, uhh, bullshittin’ around at Charlie’s?”

Arguello: “No.”

Restaurant meeting:

Williams told Arguello that the housing project he was lining up council votes for was similar to a previous development that had paid Williams’s company $275,000. The city had waived $80,000 in fees on it, and Williams stated he planned to secure $600,000 in city funding on this current project. Williams said the hitch was that Councilman Mark Paulson couldn’t vote on the deal because he’d sold Williams’ company the land for the project. Williams also said he’d discussed with Frank Liu, his business partner, running against Moreno in the next Council race, but holding office would mean putting the project in someone else’s name.

Williams: “I still need one of you guys” (Arguello or Moreno) to vote for the development … “So here I am. So I just decided, fuck all this … I don’t care who’s on whose side; I want to put this together. I want to do right by the guy (Arguello) that I’m working with here.”

Williams gave Arguello the money outside, saying, “Here you go, enjoy.”

Arguello: “We’ll talk.”

The Pasadena Weekly published a shorter version of this story. Copyright Chip Jacobs