By the time she settled into her South Pasadena dream house, Lucretia Garfield was a longtime member of an exclusive, bloodstained club uniquely American. Besides her, only Mary Todd Lincoln and Ida Sexton McKinley had stomached the horror of being the widow to an assassinated president.

Though it’d been a quarter century since a deranged stalker with an ivory-handled pistol mortally shot her husband, James A. Garfield, in a Washington, D.C. train station, Lucretia out west continued mourning the loss of her college-sweetheart-turned-spouse. In public, the hollow-cheeked septuagenarian with short, curly locks and austere expressions frequently swathed herself in dark clothes, per Victorian tradition, accenting it with a medallion in James’ honor.

Her moniker: “The Lady in Black.”

The daughter of a carpenter-farmer from Hiram, Ohio, Lucretia never desired that grim legacy. Who would? She was well educated and curious, a onetime teacher reputed to be a more talented orator than even her husband. Neither was born from privilege, and both were gifted thinkers. James, it’s said, solved the tricky Pythagorean theorem (when he wasn’t leading a country still recovering from a decimating Civil War).

Lucretia’s mettle was never open for debate, not after she survived the deaths of two children, a case of malaria, or discovering that her tall, bearded partner—a former college president, Army colonel, and congressman—once had a New York City mistress. As First Lady, the fetching Midwesterner with wide-set eyes studied up on White House history before making two brave decisions: ending the ban on alcohol there but biting her tongue in support of woman’s suffrage, despite her convictions about female empowerment.

None of that mattered after Charles Guiteau, a failed lawyer, preacher, and political hanger-on, shot forty-nine-year-old James point blank on July 2, 1881, as James was setting off for vacation. Guiteau, miffed that Garfield had refused to award him a diplomatic post, self-delusioned that God wanted him to pull the trigger, had carefully planned this execution. Train passengers immediately surrounded the assassin, shouting, “Lynch him!”

Doctors, fearing the twentieth president wouldn’t survive what was actually a survivable wound from a bullet lodged near his pancreas, made things worse by triaging him with unsterilized fingers and instruments. The lead physician continued botching the treatment, over-medicating Garfield with morphine, quinine, and alcohol. When repeated operations searching for the slug failed, the sawbones enlisted Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, to help with a primitive metal detector that Bell called an “induction balance.” The device might’ve pinpointed the slug, if the metal springs of the president’s bed hadn’t caused interference, or if the physician allowed Bell to apply the device on the correct side of Garfield’s body.

Lucretia, nobody’s pushover, wasn’t passive about her husband’s declining condition. She insisted that their family doctor—a woman M.D. she trusted—be allowed to assist the men, and that Congress pay her as much as them for her efforts.

Now riddled with infections and abscesses, the president was ferried to the New Jersey shore in dire hopes the sea breezes could do what the experts failed to: rejuvenate him. They wouldn’t. He died on September 19, 1881, having served for just two hundred days. Nine months later Guiteau, who’d pled insanity, was hanged for his crime.

Sympathetic Americans donated $360,000 for the family’s welfare. For the next twenty- odd years, Lucretia focused on being a parent to her abruptly, father-less children. Still, James occupied the prime real estate in her heart. To honor their joint passion for literature, she added a large wing onto their home outside Cleveland. It became the country’s first presidential library. A fireproof vault held James’ papers.

After Lucretia’s offspring grew, she coveted a change in scenery. So, she contracted for a steep-roofed, open floor-plan-chalet on shady Buena Vista Street in South Pasadena. The architects she selected were distant relatives who knew their way around a blueprint. The Greene brothers were innovators of the head-turning Craftsman-style home.

Lucretia, penny-pinching and opinionated about the design, regularly corresponded from Ohio with Charles Greene. In one reply to her, he admitted being distracted by a birth of a child, whom he confided he thought was “homely.”

“Couldn’t the projection of the second story,” Lucretia asked him in another one of her detail-oriented letters about the project, “be continued just a little in a flat roof underneath the cornice?”

Charles trod gingerly responding. “The reason why the eaves project from the gables is because they cast such beautiful shadows in the bright atmosphere. Of course, if you” desire “to have them cut back,” I’ll oblige.

Before the five-bedroom, shingle-sided house was completed, Lucretia lived in a residence off Orange Grove Boulevard, nexus of Pasadena famed “Millionaire’s Row. May 1903, however, proved she wasn’t just another famous person in a town sloshing with acclaimed astronomers, inventors, artists and “wintering” tycoons. It was that month that Teddy Roosevelt’s train barreled in on a West Coast swing.

The war-hero president was given a whirlwind itinerary. Stops included a trip to the region’s first luxury accommodations, the hill-mounted Raymond Hotel, the Throop Institute of Technology (later-day Caltech), and the Arroyo Seco, where he admonished Pasadena’s mayor to preserve the valley’s natural splendor. Following a rousing speech under a floral banner exalting his successful Panama Canal negotiations, Roosevelt the paid his respects to the perpetual lady in mourning; some believe it was Lucretia who invited him to Southern California in the first place. “A short visit was made with this noted lady and a toast drank to her by the President,” according to a record of their meeting.

Lucretia must’ve felt honored by his presence, if also rocked by déjà vu; Roosevelt himself had vaulted into the White House after an anarchist murdered his boss, President William McKinley, two years earlier in Buffalo, New York. In the ensuing years, it was said no major dignitary would depart town without trekking to see the Lady in Black, whose 4,500-plus-sqauare-foot Greene & Greene has long sat on the National Register of Historic Places. In her dotage, she traveled, continued championing Roosevelt, and volunteered with the Red Cross when World War I broke out. It’s not apparent how much, if ever, she sampled the local attractions, be they Rose Parades, Busch Gardens, Clune’s Theater, the Mount Lowe Railway or the Cawston ostrich farm nearby. One can hope it was a sunny coda for her, nonetheless.

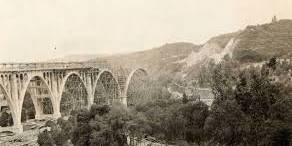

Lucretia died in her South Pasadena sanctuary in March 1918— five years after the Colorado Street Bridge accelerated the automobile age, and decades before Jacqueline Kennedy joined her particular dead-husbands club.

Related Posts

South Pasadena Cawston Ostrich Farm, where strange birds made sawbucks

Watch this slick, little documentary about the ostrich farm…

U.S. Scolds Pasadena Police Over Drug Funds

Los Angeles Times Purchase of five cars for senior officer…